Researching one’s family can be extremely exciting, addicting and rewarding. It also involves some hard work, dedication and a big desire to want to know. There are times when it can take years to compile a family. There are also times when a family history falls into place with relative ease.

Creating an accurate family tree or history is much like putting together a very large jigsaw puzzle – some pieces are easy, and some are a challenge to locate. It is important to be sure that all pieces fit on all sides. If you force a piece into the wrong place because it looks right and should fit, there will be problems down the road. Family histories are no different. No one wants the wrong person placed within a family if they don’t belong there.

Having stated this, you may now be asking – Where do I begin? How do I start to study my ancestors? Well, surprise - there is a process for this.

The Genealogical Proof Standard

The Genealogical Proof Standard:

Creating family histories and similar products is nothing new. People have compiled genealogies for centuries if not millennia, although in different formats than are used today. Good research is soundly reasoned from evidence. Good reporting or writing cites its sources sufficient for others to be able to locate the information. Advances in product and process standards have led to the field’s best practices. These are defined by the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS).[1]

- Reasonably exhaustive research – emphasizing original records providing participants’ information – for all evidence that might answer a genealogist’s question about an identity, relationship, event, or situation

- Complete, accurate citations to the source or sources of each information item contributing – directly, indirectly or negatively – to answers about that identity, relationship, event, or situation

- Tests – though processes of analysis and correlation – of all sources, information items, and evidence contributing to an answer to a genealogical question or problem

- Resolution of conflicts among evidence items pertaining to the proposed answer

- A soundly reasoned, coherently written conclusion based on the strongest available evidence

“A genealogical conclusion is proved when it meets all five GPS components. Each part contributes to a proved conclusion’s credibility.”[2]

If any of the five parts of the GPS are not met, the conclusion has not been proven.

Just like in any other field of study - whether one is searching or researching, as a hobby or professionally, for yourself or for others, it is necessary to abide by and pay attention to the standards.

[1] Board for Certification of Genealogists, Genealogy Standards, (Washington, D.C.: Ancestry.com, 2014), see Chapter 1.

[2] Ibid, 2, 3.

How to do Genealogical Research:

- Start with what you know. Right it down. Record it in a method of your choice. What you know includes names, places, dates. These three items – names, places and dates – are the foundation, the skeleton, the framework of genealogical research.

- Be sure to record why you know these details. There is nothing worse than saying, “I know I saw that someplace - where and why can’t I find it? Who said that?” (these elements are part of a good citation).

- Review information that you have. What birth, death and marriage certificates do you have? Funerary cards? Birth announcements? Labeled photos? Bible records? Family artifacts?

- Be sure to record what this evidence is. There is nothing worse than saying, “I know I saw that someplace. Where is it and why can’t I find it? What exactly did it say? What was that record and where did it come from?” (these elements are part of a good citation).

- Interview your relatives and if they grant permission, study what they have. Determine what you want to know ahead of time and write it down. Be flexible, however, during the conversation to allow room for new information to be explored. If time does not allow you to get to all your questions, try and schedule another time to get together.

- Be sure to make note of what you learned and how they (your relative) knew these details. There is nothing worse than asking after the fact, perhaps after it is too late, “How did they know that? Why didn’t I write that down?” (these elements are part of a good citation).

- Record your information as you come across and study it – cite your information. It is an uncomfortable time when you know you learned something and discover you do not know how to relocate it. If you can’t return to it, how can you guide others to the same information?

- Once you have collected the “low hanging fruit,” it is time to search repositories of information (i.e. websites, courthouses, cemeteries, churches, libraries, etc.). At some point you will move from searching to researching. It is not uncommon to move between searching and researching – searching is the browsing; researching is the digging in and looking for evidence that answers a specific research question. Cite the Information gathered everywhere you look.

- Compile a report, including citations, of what you have learned and hopefully share it with others.

Just like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, families are best tackled one person at a time, one item at a time. What is it that you want to know about any given ancestor or relative? Be specific. Develop an action plan beginning with a good research question. Good questions are not too broad nor are they too narrow. They provide focus. For instance, say you know your grandmother was born in 1915 in Pennsylvania, daughter of Ben and Mary Smith, but you do not have a location. Your question could be, “Where in Pennsylvania was Betsy Smith, born in 1915, daughter of Ben and Mary Smith, born?” A question like this provides clarifiers (a year and parents) that could prevent you from mixing up one Betsy Smith with a different Betsy Smith. Then decide where are the best places to locate this information that leads to evidence and dig in.

Remember, cite what you say and say what you cite. Hearsay such as Aunt Susie said that Uncle Charlie said that cousin Emily said is not evidence by any stretch of anyone’s imagination. That said, hearsay can be used as a lead for additional research.

Speaking of evidence – keep in mind that information is information only. It does not become evidence until it is used to answer a question or problem.

Forms, Charts, and Genealogical software:

There are many different forms, charts, tables, and tools that are used for organization. They include pedigree charts, family group sheets, relationship charts and genealogical software. For every record type and activity, there is probably a form somewhere.

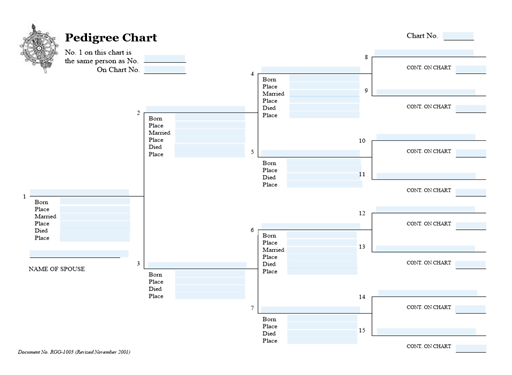

Pedigree charts: Pedigree charts are a must for any genealogical project. They provide a quick visual of how a family fits together and highlights at a glance where there is missing information. An easy search on the web for “pedigree charts” will provide many options for downloadable or printable charts. Some are better than others. Look for a blank chart with numbered ancestors. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) has a good example of a blank pedigree chart at https://www.dar.org/sites/default/files/RGG-1003.pdf.

Pedigree charts are filled out in a specific manner.

- You are No. 1.

- Your father is No. 2 and your mother is No. 3.

- Your father’s father is No. 4 and your father’s mother is No. 5.

- Your mother’s father is No. 6 and your mother’s mother is No. 7.

- Males are always even numbered, on top, and females are always odd numbered and on the bottom.

- Fill in as much information as you know and have evidence for.

- When you reach the end of a line on any chart, the line is continued on another chart.

- For example, Person No. 8 (your great grandfather on your father’s side) could continue on Chart No. 2 as person No. 1.

- The information on Chart No. 2 would state that person No. 1 on this chart is the same person as No. 8 on Chart No. 1. or maybe Person No. 1 on Chart No. 4 is the same person as No. 13 on Chart 1.

- Be sure to number your charts. Note that a complete Chart No. 1 will generate 8 additional Pedigree Charts.

- Women should always be recorded using their maiden name. If this name is not known just use her first name.

- Any information that you do not know, leave blank.

- Family group sheets: Family group sheets are used to record information about a specific family, i.e. your grandparents and all their known children. Generally, Family Group Sheets include places and dates of birth, marriage, death, and possibly other types of information about an individual. An example of a blank Family Group Sheet can be found at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) website at https://www.archives.gov/files/research/genealogy/charts-forms/family-group-sheet.pdf.

- Research log: Searching and researching can quickly get out of control if not organized. It is important to keep track of where you have been, what you have looked at, and what you have found. This will help with citations as well as remind you where you have already been, so you do not unintentionally duplicate work. The best way to do this is to use a log of some sort. Familysearch.org has a free downloadable research log,

https://s3.amazonaws.com/ps-services-us-east-1-914248642252/s3/research-wiki-elasticsearch-prod-s3bucket/images/5/50/Research_Log.pdf - Relationship charts: These are charts that help determine relationships with a relative. For instance, people who share first great grandparents are considered second cousins. If my 1st great grandparent is your 2nd great parent, then we would be considered 2nd cousins once removed (2C1R). Cyndi’s List has a page dedicated to relationship charts at https://www.cyndislist.com/cousins/charts/?page=2.

- Genealogical software: Genealogy programs are an excellent tool to keep track of your data. Most will provide some type of citation format, forms, charts, reports and a relationship calculator. Choose one that best meets your needs but don’t be surprised if you try a few before you settle on a specific program. A recent comparison of the most popular programs can be found at http://www.toptenreviews.com/software/home/best-genealogy-software/. Keep in mind that there are other programs available than those listed here. In addition, there are sites,such as FamilySearch.org, that allow you to create your tree(s) on-line for free.